When I was approached by the PROOF collective about potentially working on a project together, I knew I wanted to do something for Grails.

For those unaware, Grails is an exhibition event wherein 20 artists are selected to submit a work of art. Individuals can purchase a "mint pass," which acts as a ticket to purchase any one of the 20 artworks. The twist is that they are neither titled nor described, and artist names are not provided. Experimentation is encouraged. Presenting a new style of work to be examined closely by bystanders attempting to figure out who made it is quite a unique experience.

In my eyes, Grails is an explicit invitation to surprise people with something different. For me, that thing was a looping, hand-drawn 60fps animation titled Doomscrolling.

Background

I quit social media for a while in late 2020. Quarantined at home with my wife and young child prior to that, I recall spending a ton of time sitting around flipping through twitter, addicted to the seemingly endless deluge of bad news.

After a while, I started to notice that the habit was changing me. I was feeling impulsive, angry, pessimistic, and a little neurotic. I deleted twitter from my phone and stopped paying attention to it completely. My family and I packed up and moved to Vermont, where I went without internet for about a month before settling in. After that, I felt more present and started feeling better. I started a new job and got on with life. The social media break didn’t last forever, but I’m a lot more guarded about endlessly scrolling now.

All that said, that time of life (mine and many others) was dominated by this awful black hole of bad news. I wanted to make art about that.

The Process

When I started making art full time, I quickly realized that I wanted to incorporate my hands into my process more. After working as a software developer for a decade, the balance of computing vs. non-computing time shifted pretty dramatically when I quit my day job. I spend most of my time away from computers these days, and the process of creating Doomscrolling reflects that new balance.

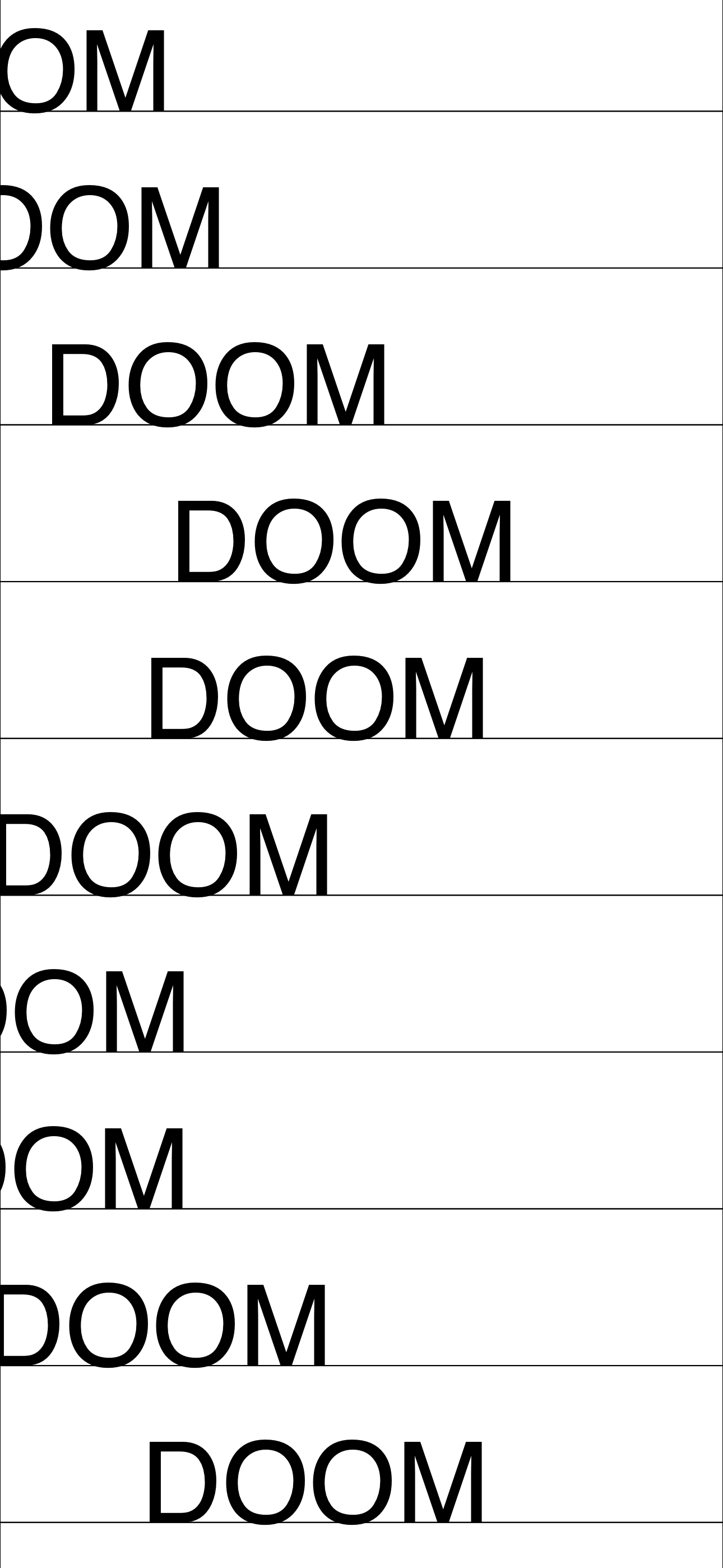

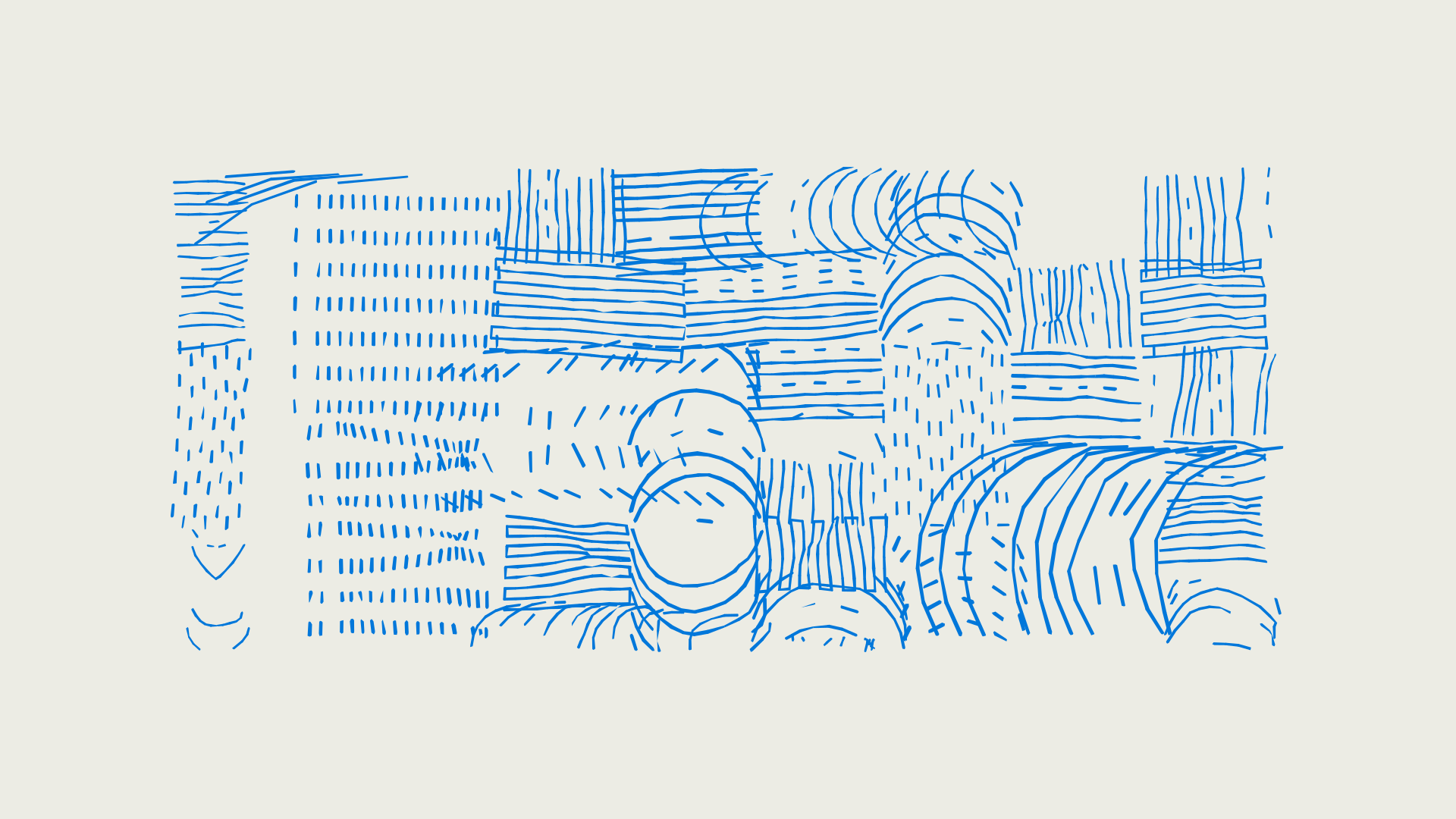

A template for the animation was created using my personal framework for making generative art, built on top of the graphics library Cairo, interfaced with via a Haskell package. The smooth scrolling on an iPhone involves applying a constant friction to the force implied by a finger swiping upwards. I have involved physical simulations like this in a bunch of my prior work, and I thought I could mimic this behavior pretty closely using the tools I had on hand. The original idea had “DOOM” on each line of an imagined social media feed and I tried a few variations of that, making the words and letters ebb and flow in a perfect loop.

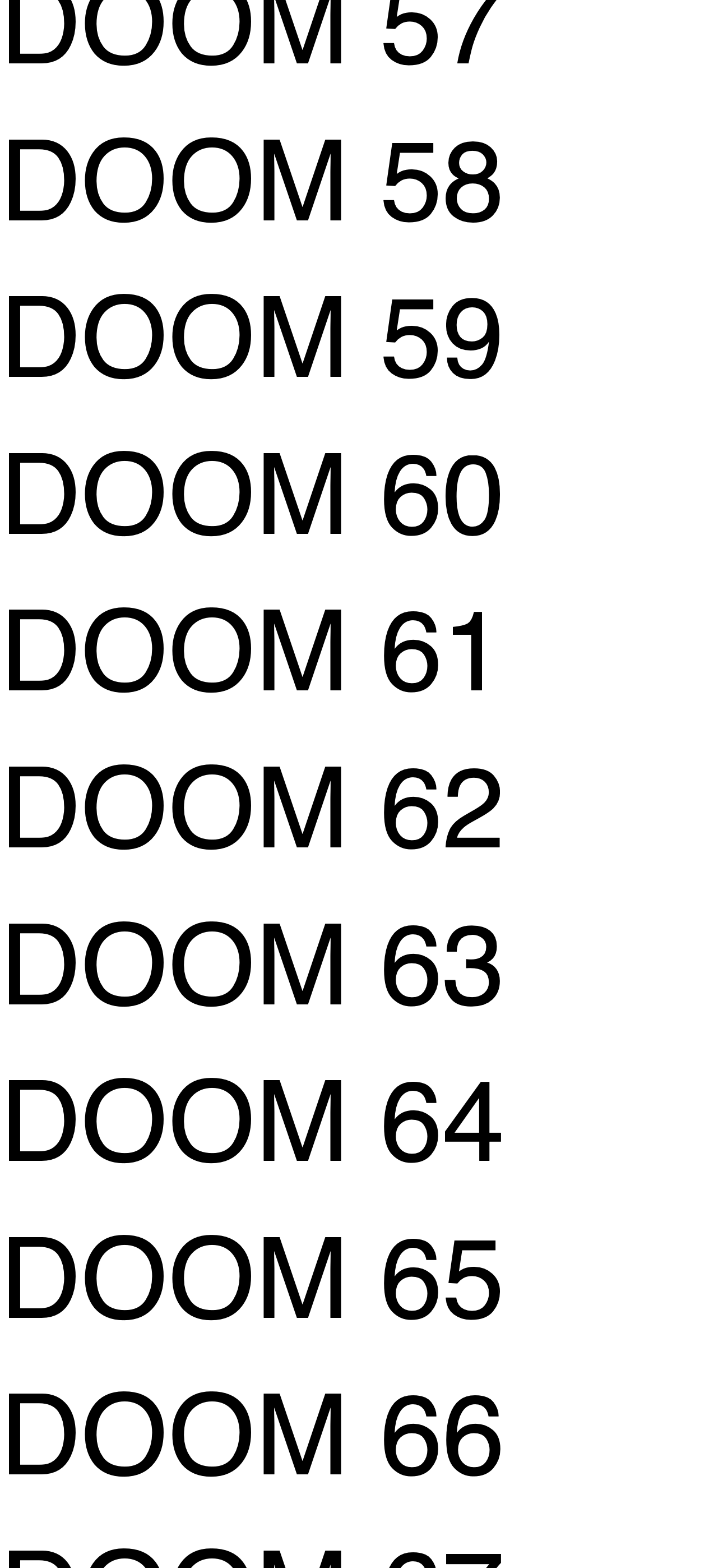

After some trial and error, I changed the animation from the original “doom on every line” to simpler imagery. From there, I fiddled around with how many “swipes” were emulated and tweaked their intensity so that the animation ends perfectly at the “M.” Once that was done, I rendered out the 300 frames individually and got to work.

Charcoal

All of the completed frames of Doomscrolling filed away.

I took an 8 week live figure drawing class this past Spring. I learned a few things about myself from that course. I missed drawing immensely, I love drawing the human figure, and I love using charcoal.

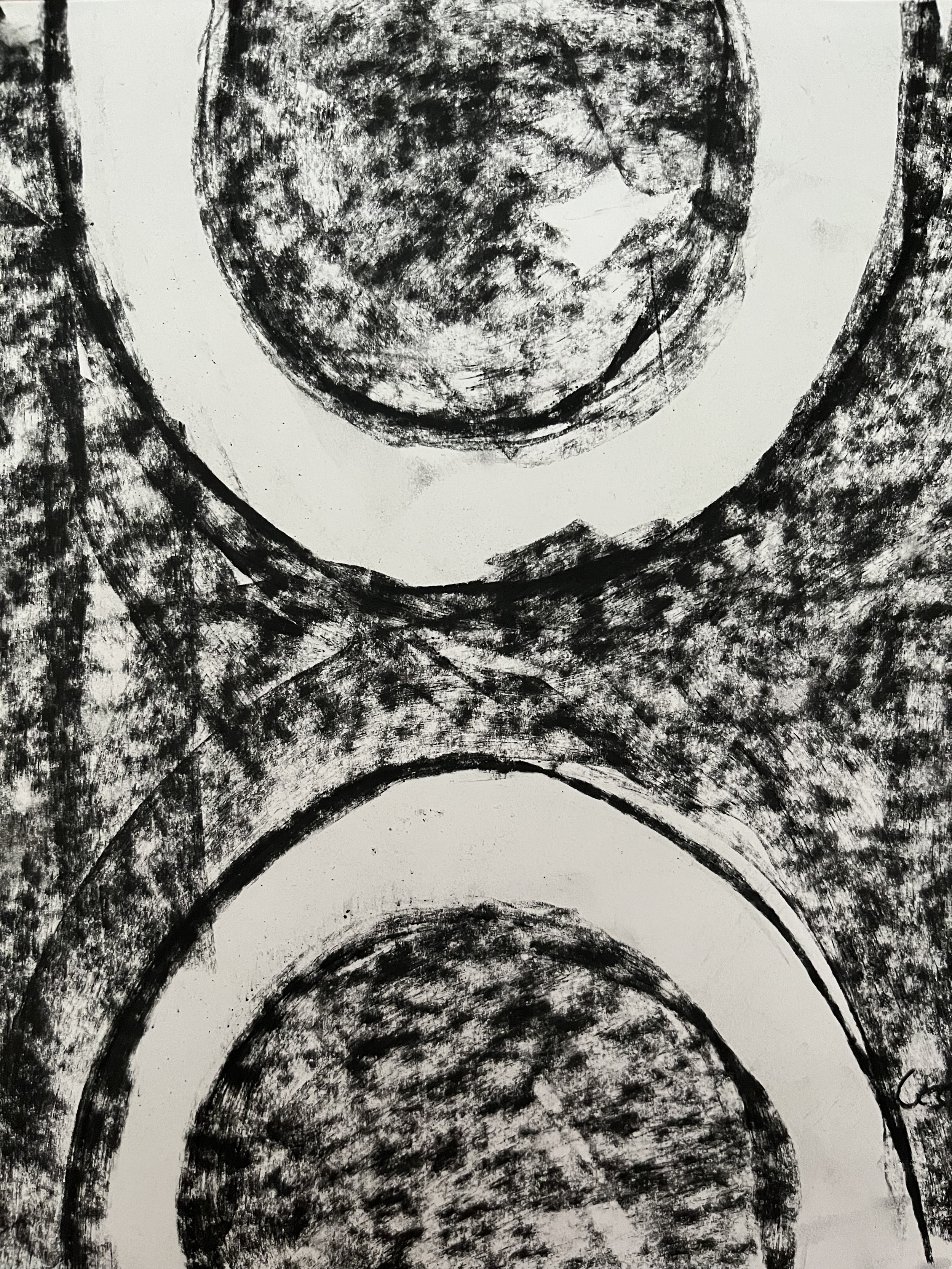

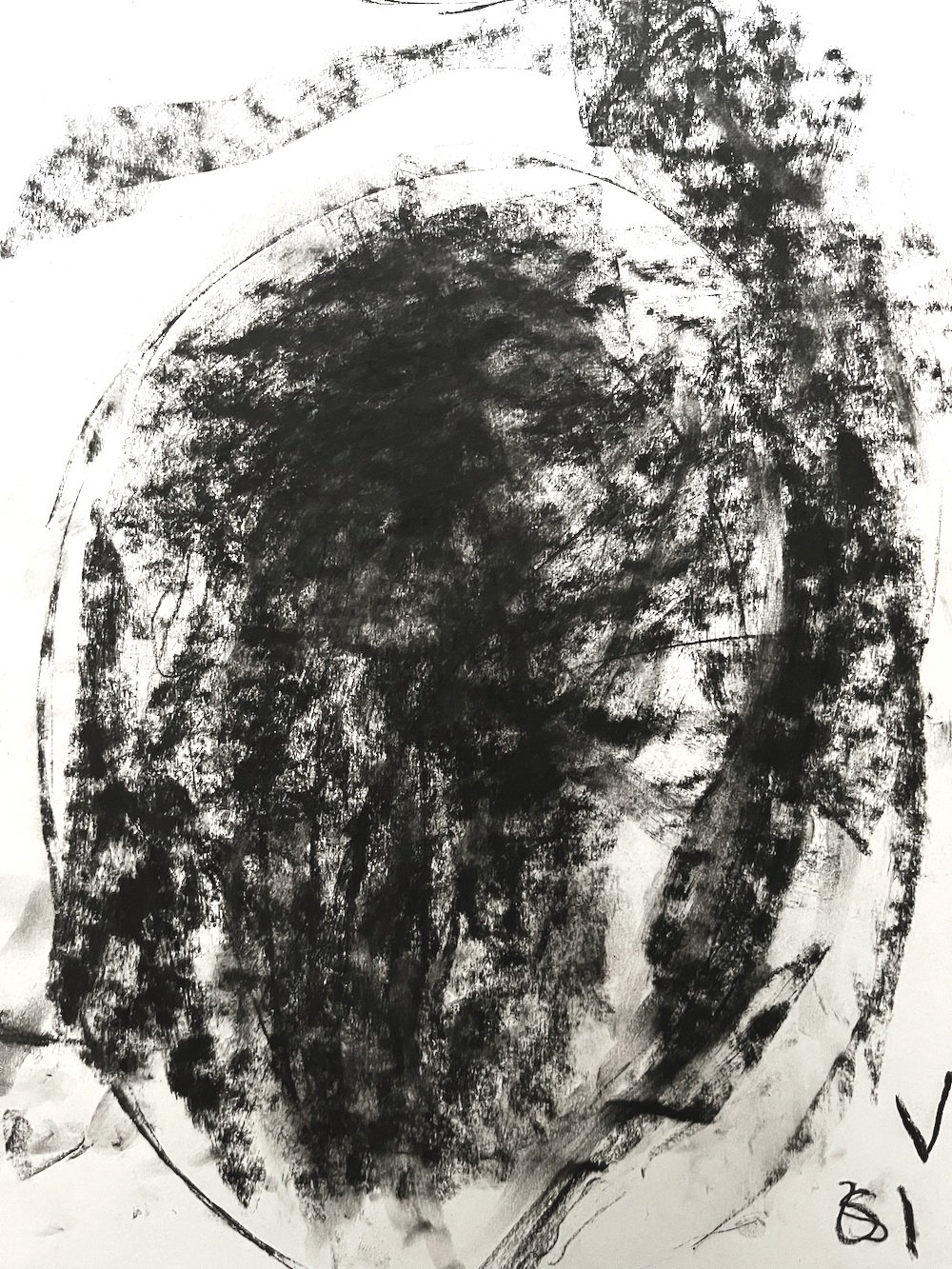

My original idea for this work was to paint each frame of Doomscrolling — an idea picked up from William Mapan, whose hand-painted processing sketches are killer. As I thought about it, though, I realized that painting 300 individual panels would take more time than I had. So I prototyped a few frames in various media and loved the aesthetic of charcoal. You can cover a lot of ground fast with charcoal. It’s cheap and produces a strong texture. It’s easy to use. So easy, in fact, that my 3 year old daughter was able to pitch in for a few frames (the V is her signature for those wondering).

I printed all 300 frames on regular printer paper, traced each one somewhat frantically in charcoal, and stored batches of 20 in a file array. I photographed each one later on my phone in natural light and compiled the images using ffmpeg. The numbers in the bottom right of each frame helped me keep the photographs straight. I tried omitting them and ended up with duplicate and missing frames, so most of the frames are numbered.

One reason I structured this project the way I did was to stop wasting time on my phone and replace it with something similarly mindless but productive and fulfilling. It worked — I spent about 15 hours drawing the 300 frames in the final product, and a few more hours photographing and in post-production. Filling those printer sheets with charcoal was a meditative time for me. You can watch me carry out this process in real time below.

Speculations

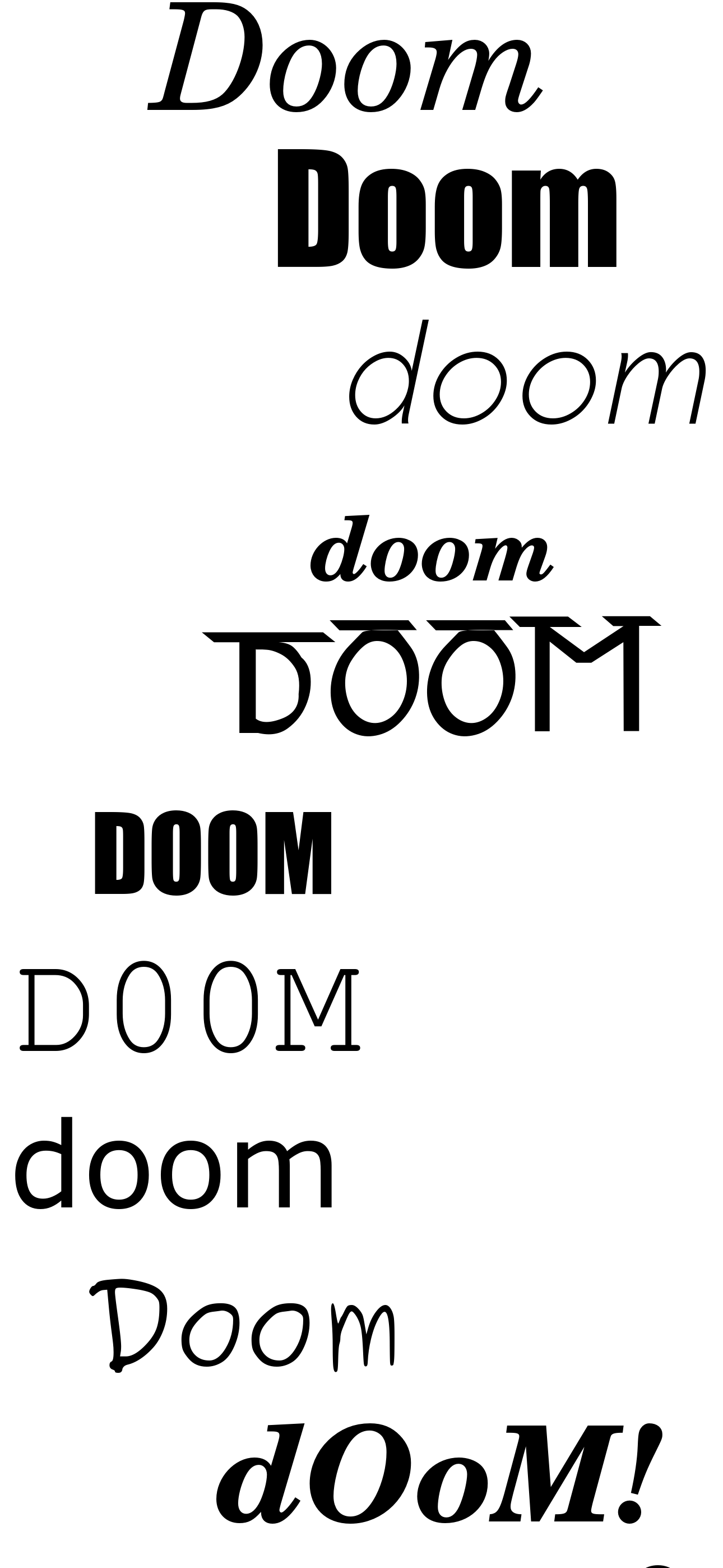

Once Doomscrolling went on view for the Grails IV exhibition, I couldn't help but lurk on Discord and wonder what people would think. A couple of days in, an initial survey hinted that a lot of people thought that the work was made by XCOPY. XCOPY’s digital work often consists of short loops with strong textures — boxes Doomscrolling does tick. However, they’re also usually figurative in some way and involve bright colors, which disagrees with the aesthetic of my animation. I was pretty surprised by the strong consensus.

That is, until I saw this.

Although it might be hard to believe, I had never seen this artwork before I made Doomscrolling.

I’m familiar with XCOPY, but not this particular piece. On one hand, I’m a little embarrassed to admit that. On the other, I’m glad I didn’t run into the work earlier. It would have deterred the pursuit of my own project. To guess that Doomscrolling is either an homage to this work, or even a new work by XCOPY himself, seems reasonable enough to me. However, it is neither: that we depicted the same phenomenon in similar ways in our work 4 years apart is a complete anomaly. It is uncanny, though, and I’m here for the synchronicity.

The work was in some ways influenced by Jake Fried, whose black and white, sketchy animations have caught my eye, and it seems that influence was picked up by some. And while I love the idea that MF DOOM came back from the dead to create the work, that isn't true either. My personal favorite guess was William Kentridge, who makes these amazing charcoal animations. I wasn't aware of his work until now and I'm grateful for the introduction by means of the exhibition. I had a lot of fun making my own guesses as well, and learned a lot by watching other collectors make their own guesses.

I’d like to thank everyone involved in putting Grails IV together as well as the collectors who dove into my work in an effort to figure out who made it. It was a very special experience.

Death to doomscrolling, long live Doomscrolling.